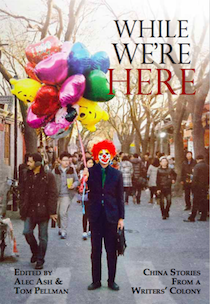

Putting your feet up

The colonialists endure – by Alec Ash

Four years ago, Alec, a 23 year old student of Chinese at IUP in Tsinghua University, put his feet up on the train seat in front of him. The carriage was pretty empty, and he was dead beat. So he peeled back a corner of the smelly blue seat covering across from him, and plopped a worn pair of Merrells on the wood underneath. This redistributed the weight from his bony arse across his legs and back. It felt great.

Like all the train rides he took, Alec was in hard seat class. He was broke. But he also liked to talk to others in the cheapest class, where conversation, cards and the obsessive consumption of nuts and seeds were the only ways to pass time. It showed him a new side to the country, and was a good way to practice his spoken Chinese. And, more than he would have admitted to himself at the time, he enjoyed the idea that he was roughing it, choosing the gritty option over the comfort of a recliner, “eating bitterness” in the real China.

It was Friday 13th November 2009, and Alec had been travelling for the last week, during his school’s half term break. From Chongqing he had taken a boat down the Yangtze to the three gorges dam, before bussing it to the provincial capital of Wuhan. That’s where he boarded this train to Zhengzhou, one province up, so he could pay a flying visit to Shaolin Temple before class restarted.

Only this train wasn’t moving. An early snowfall had held it up on the outskirts of Zhengzhou for the last eight hours. Daylight was disappearing, and Alec would have to spend the night in the metropolis, rather than at Shaolin. He was beginning to regret this final leg; he could be back in his flat in Beijing by now.

Despite the fresh snow outside, the inside of the carriage was stuffy. All the windows were locked for the passengers’ comfort and safety. The floor and upholstery were encrusted with seed shells, which made the carriage smell of cereal. Although it was less than half full, there were enough bodies to add the scent of BO, on top of whatever was wafting through from the toilet at one end. Everyone was getting restless.

Alec buried his head in a book, to avoid conversation. He could feel, in his peripheral vision, a Chinese man staring at him from the other end of the carriage. He risked a glance, and two things happened. First, Alec realised that the man had been waiting for eye contact as a pretext to get up and start a conversation with the foreigner. Second, the man got up, walked over to him, and did just that.

“Niiii Haaow!” – the man enunciated as if talking to a deaf two year old. He was bald, middle aged and clearly a migrant worker.

Alec gave what he judged the bare minimum to acknowledge the man – a half-smile and grunt – before returning to his book. For all his bravado about riding hard class, its charm had worn off after sleeping in his chair last night. He was not in the mood to talk.

“Niiii Haooow.” The man repeated his opening gambit, and this time laughed loudly as if it were a wise crack. He had crooked yellow teeth, knock-out bad breath, and the lines on his forehead crumpled up when he spoke. He was obviously bored out of his skull, and just curious.

Alec kept his feet up. He was determined not to be disturbed, and didn’t want to give this man a chance to sit opposite him. The man batted at Alec’s shoes.

“Excuse me,” Alec said in Chinese. “I’m reading a book.”

The man gasped theatrically. “You – can – speak – Chinese!”

Alec saw his error, and knew he was in for the long haul. The usual questions flew. Was he a student? Where was he was from? Did he like England more or China more? Was everyone rich in England? Did everyone have two cars in England? Does it snow in England too?

Alec’s answers were curt, and delivered with the defensiveness of someone whose Mandarin isn’t yet comfortable – not “Yes” but “Of course!”, over-pronouncing the tones. The man’s reaction was unvarying – “Your Chinese is so good!” – yet he still spoke slowly, fearful of not being understood. Alec was both pleased and irritated by the hollow compliment.

The one-way conversation switched between the man’s half-formed ideas of England and his name dropping of Chinese historical figures (“Do you know Zhou Enlai? How about Hu Shi?”). Alec got the impression he was showing off that he was educated, that he knew about overseas, in the same way Alec liked to show he knew about China. But Alec barely acknowledged him, trying to make the hint stick that he wanted to be left alone.

Everyone in the carriage was watching the conversation now, of course. The man persisted, but was put off by the reluctance of this foreigner to engage. He was losing face in front of his friends – and beginning to look like an idiot. He pulled out his trump card.

“England was a colonialist country. The English were colonialists.”

He looked back to check that the crowd had heard him, his remarks as much for them as for Alec alone. His tone had changed with this slightly more unfriendly remark, as if he was proving a point now, and no longer just killing time.

“You’re a colonialist!”

It was delivered more like a joke than an insult, the way you might rib a friend. Perhaps the man used that tone because he thought Alec wouldn’t understand the word, and that he could make the joke at the foreigner’s expense, without being caught.

But Alec had learnt the word – zhiminzhe – at his school just last month. He wasn’t offended, of course. It was ridiculous and funny to be called a colonialist. He could already picture how he would tell this story to his friends in Beijing. But he too had sensed the crowd forming, and wanted to show them that he did understand, that he could hold his own in Chinese.

“Mister,” Alec started, using a word which is polite but a bit awkward and old-fashioned. A colonialist? How silly. Colonialism was a system that existed in the British Empire during the 18th and 19th centuries – his new vocabulary was coming in useful, thanks to the textbook Thought and Society 1 – so how could he be a colonialist?

The crowd snickered, and looked at the man for his reaction. He was getting shouty now, and started to point. He accused England of invading America and India. He took Alec’s book and wrote, in the back, “Why do English jobless people come to make money in China?” (为什么英国无业人在中国发财?). Alec let him blow off steam without conceding the point. He began to sense the crowd was behind the man now, and felt less safe.

They must have been getting loud, because a train attendant arrived and led the man away. He sat down at his end of the carriage, and stared. Later, some students Alec had been talking to earlier came back, and said they were going to get off the stationary train to find a bus into Zhengzhou. Alec gathered his things, went with them, and avoided eye contact with the man as he stepped off the train, breathing in deep icy relief.

***

Every time Alec remembered that scene over the next few years, a detail was different – the colour of the man’s teeth, the smell of the carriage, the precise nature of his bad mood that day. Some parts he distrusted, as if his memory had polished them first. Above all, he questioned if he had acted badly, arrogantly. What exactly had he said when accused of colonialism? Had he been reasonable, or condescending?

It particularly irked Alec that he wasn’t sure at what point he had taken his feet down. Was it after the man had first batted at them? Or did he keep them up, and only take them down later, if at all? Had the man swatted them to remind him it wasn’t polite to have them there while talking? Or was he just trying to get his attention?

When he looked up what he had written in his journal on the day, Alec was surprised to find that the man had been sitting throughout the whole exchange, and not standing as he remembered it. He had clean forgotten that the man had mentioned Zhou Enlai, or that he had written such an odd, accusatory thing in the back of his book. It was only through a combination of those notes from the time, and his memory now, that he could massage the story into a narrative, to say “this is what happened” – or the closest thing to it.

But one particular forgotten detail blind-sided him. “He was a dick,” Alec had written of the man, “but I don’t know what he’s been through in his life. Only one thing he said struck a note and left me silent. 中国穷. China is poor.”

In reading that, Alec remembered the man saying it, out of context towards the end of the conversation. As then, he had no reply to it now, no way around how obvious his privilege must have appeared to the man’s relative poverty – how the young foreigner who didn’t want to talk was in the cheap class but did not belong there, and had another choice.

And writing about the whole thing now, four years later in his heated Beijing apartment on an idle evening with his feet up on a piano stool, he felt ashamed.

•

Alec Ash is a writer and freelance journalist in Beijing