Help us continue to publish original stories from China by donating!

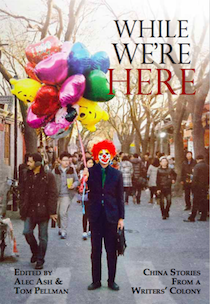

Read our anthology

Link of the week

A new China Channel from the LA Review of Books, for Sinophiles and the Sinocurious alike

Quote of the week

“China is a big country, inhabited by many Chinese.”

– Charles de Gaulle

Ants in the hill

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  | > See all |

Most popular antics

About us

A writers' colony of stories about China, founded by Alec Ash. We publish non-fiction sketches, fiction, poetry, translation and photography

Join the colony

If you want to write for the Anthill, check out our submission guidelines. Anything with a sense of story is game, both short and long form

Sites we like

For more treasure troves of narrative writing, fiction, photography, poetry and translation from or about China, explore other sites we like

We're a 2014 Danwei Model Worker

Shortlisted for a Golden Giraffe

Testimonials

“People fortunate enough to live in China have a front-row seat to an astonishing transformation. Alec and the crew at the Anthill have been there to give voice to their musings on China, in all its weirdness, wonder and warts."

- Kaiser Kuo

"Everyone who lives in China has a story. The Anthill colony of writers have the foresight to write theirs down for the entertainment and enlightenment of all of us engaged in putting the pieces of the China puzzle together.”

- David Moser