Out of Tibet

One Tibetan's story, caught between identity and modernity – by Alec Ash

When Tashi calls, I am in a temple overlooking Xining, the capital of Qinghai Province in western China. Loud, slurred, distraught, he asks me to come quickly.

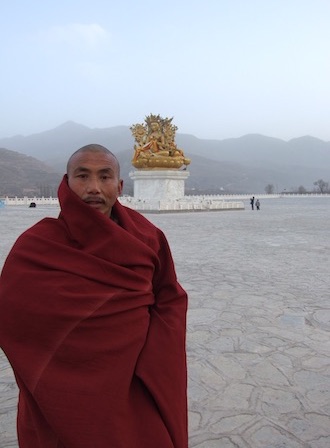

Tongren, or Rebkong in Tibetan, is eight bumpy hours south, high on the eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau, and the next bus is at noon. When I arrive, it is dusty evening. Tibetans in cowboy hats or Adidas beanies walk the markets, where Hui Muslims in characteristic white hats sell fried chicken and chilled Coke to Han Chinese immigrants. Monks from the Tongren monastery stretch their legs, trainers poking out from underneath their dark crimson robes. Although this region is not politically defined as Tibet (“China’s Tibet,” the autonomous region established by Beijing in 1965, is many miles to the southwest), ethnically and historically, it is firmly Tibetan. It is Tibet out of Tibet.

I find Tashi in a bar on the outskirts, in the middle of a self-hating drunk. He is in his mid twenties, with dark Tibetan skin, brown puppy dog eyes, and a greasy waterfall of black hair. On the table in front of him is a small Everest of cigarette butts and a display of beer and liquor that would make the poet Li Bai, famous for his verses on wine, blush.

“I’m an animal,” Tashi says, looking up. “She left me.”

***

I first met Tashi—not his real name—eighteen months before that night, in his home village of Shuangpengxi, half an hour’s drive northeast of Tongren. To go there by taxi costs fifty yuan (about US$8), but passengers often pool together so that no one pays more than the cost of noodles and a beer. Taxis making the return journey are scarce, so you’re better off hitching a lift, squeezed in between a grinning nomad and his dog, or holding on for dear life in the back of a pickup.

Shuangpengxi (also known as Zhoepang) is, for now, the calm eye of a materialist storm that Chinese modernization has brought to many other areas of Tibet. It is set on a gentle incline, sloping toward yellow barley fields, with a swift, shallow river at its base. A wooden temple at the village heart punctuates low rooftops and brittle wooden racks where animal skins dry in the hot sun. On one side of the mountain face, watched over by brightly colored prayer flags, is a new middle school, whose brick walls, painted red, look unnaturally clean against the village’s clay houses and twin stupas.

In the summer of 2007, fresh out of university, I was amazed to find myself in such a windswept, Lost Horizon location. I called it Songpongshee, in my best monkey-hear imitation. Later, as I began to learn Chinese, I discovered that the name Shuangpengxi means “two friends in the west.” I was there with five British friends. We were English teachers at a new school built in 2005 through the generosity of French donors who had studied Buddhism in Nepal. A hundred or so shy Tibetans between the ages of ten and eighteen were in our charge. Their numbers decreased steadily as “summer religious festivals” drew them back home. We soon realized that these holidays were almost entirely made up.

As the weeks went by, the floor of our dorm slowly filled up with dry bread buns, empty fruit beer bottles, and a carpet of multicolored paper scraps left over from various activities. We rose too early for our liking and taught through the morning, with sport, art, and drama options in the afternoon.

In the evening, we walked into the village to eat dumplings with new local friends, or to buy vegetables to stir-fry ourselves. On days off, we explored the mountains on either side of the school. Sometimes young monks from a nearby monastery would come down to play basketball with the foreigners, dirtying their ankle-long robes.

In the evening, we walked into the village to eat dumplings with new local friends, or to buy vegetables to stir-fry ourselves. On days off, we explored the mountains on either side of the school. Sometimes young monks from a nearby monastery would come down to play basketball with the foreigners, dirtying their ankle-long robes.

When Tashi heard that there were foreign teachers in the school, he came by to introduce himself. He was dressed in flared jeans, a shirt, tie, and waistcoat, with a heavy sheepskin coat over it all. By turns shy and boastful, he invited us to his home for tea with yak butter, cheap cigarettes, and tsampa, a Tibetan staple food made out of barley. Later, we went to his girlfriend Lhamu’s larger house, where we watched Michael Jackson videos on a crackly color TV.

Tashi and I became fast friends. When my classes ended, the two of us traveled to his best-loved grasslands in a neighboring province. A white horse was roaming the fields when we arrived, and Tashi jumped up to ride it bareback, though when I tried the horse just kicked me off my feet. As a picnic, we bought a rump of yak, the corresponding weight of bread buns and (at Tashi’s insistence) twenty bottles of beer. Beer bottles in China flirt with the liter mark. Tibetans deserve their reputation as formidable drinkers, and Tashi is no exception. Taking huge power gulps and chugging through smoke after smoke, he began to really talk.

***

Tashi’s father and mother were both fifteen when he was born in 1983. Fifteen years later, in one of life’s symmetries, Tashi married, and a son was born. The marriage had been decided on by Tashi’s grandfather a good many years before that. The bride’s family was rich and held high status in the village. But neither Tashi nor his new wife was happy. “At that age,” Tashi says, “you don’t know anything—what is love, what is marriage, nothing. But there is no choice. Custom is more important."

The couple also shared a secret. The child was not Tashi’s son at all. For the first two years of their marriage, Tashi slept in the same bed as his wife but they did not have sex. Only the boy’s real father and some village elders knew the truth. Everyone else assumed that the child was Tashi’s.

Four years later, Tashi’s grandfather died. Tashi’s wife—none too discreetly—found another boyfriend. This time there was no secret. Everybody knew, everybody gossiped. Soon after, she left their home to move back in with her parents. Tashi tried to persuade her to come back. A month passed before he found out why she had left. She was pregnant again, and she insisted that the child was his. Three months into her pregnancy, against Tashi’s wishes, she had an abortion. Tashi divorced her. He was not twenty.

To escape this sour episode, or perhaps out of simple wanderlust, Tashi took off. There was nothing to keep him in Shuangpengxi. Estranged from his mother and father, who had sent him to a monastery when he was three (he left at seven to go to school), he was close only to his grandmother. Young and ambitious, he felt he had more to see than what his village could show him.

Tashi studied Tibetan history and English for three years in Xining, then Chinese for a year in Beijing. At first he went home once a year to celebrate Losar, the Tibetan new year, with his grandmother. But his fifth year away, Tashi didn’t make it back. He was busy exploring the bright lights and romantic prospects of Shanghai, and (fruitless) business opportunities in Shenzhen near Hong Kong. In Sichuan, he got in trouble for restoring a sign marking the historical border of Tibet – in prison for a few nights, he claims he was fed tsampa with mouse droppings inside, which made him violently ill. He taught English in Xining, and opened an art school in the nearby Kumbum monastery. He traveled to Lhasa and worked for a month as a scribe, tracing golden ink over fading letters in a monastery library.

When I first met Tashi in that summer of 2007, he was twenty-four and in Shuangpengxi for the first time in a long while. Back from the grasslands, and somewhat worse for wear, we retreated to his house on the outskirts of the village. The following morning, I asked Tashi to make good on a drunken promise from the day before and write me a poem.

Obliging, he sat cross-legged on the heated platform of his room, where a hard mattress formed his bed. Like a schoolboy, he had plastered posters on his walls, but instead of footballers, the blue Buddhist god Tara sat in the lotus position, framed by two fake stuffed birds and a miniature ram’s head. To their left was a large landscape poster of Lhasa, with Potala Palace unmistakable at its center. The fourteenth Dalai Lama, its former resident, looked down from above it, framed by a white ceremonial scarf, or khata. The Dalai Lama is still a familiar face in Tibetan homes and the bolder monasteries, despite the Chinese ban on his image.

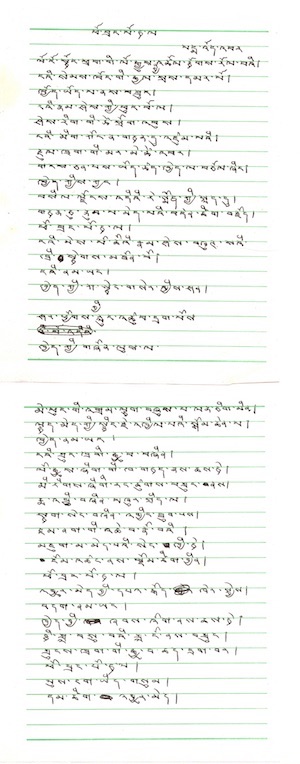

Scratching diligently on a sheet of paper with my fountain pen, Tashi wrote for thirty minutes, the crumpled spiders of his Tibetan characters hugging their lines from below, vowels hovering over every third or fourth consonant like halos. Later, I asked an ethnic Tibetan who teaches at Oxford University to translate the poem for me. It is called “Potala Palace”:

Red prince of my heart

That quenches my thirst for the history of a thousand years

In your presence sprouts the life force of knowledge

In the garden of my consciousness.

The eternal flame of the butter lamp that flickers in my eyes

Is stoked by my sweat and blood.

The land of snows has entrusted everything to you

And you too fearlessly speak the word of truth

For the sake of our hopes and prayers.

Potala Palace!

The consciousness of my forefathers rests on your high throne.

I forever will decorate your pillars with golden rings.

But the fierce wind from the East

Has many times racked with tongues of flame your tender form.

O great yogi, in whose heart swirls unadulterated compassion

You forever, like the blood moving in my body

Will rise to face the challenge of history.

Embodying the integrity of a nation

Even though you are hurt you lick your wounds

And stand proud in all circumstances.

While the sharp fangs of a dark beast

A tailless dog pretending to be a lion

Utters empty threats from its cave.

Potala Palace!

The solitary hero, never changing.

I forever will serve under your blessing.

Potala Palace!

From the first time I welcomed the sun and the moon

Until when the circulation of my blood stops

My loyalty to you in body, speech, and mind

Shall remain eternal.

As he handed it to me, Tashi smiled sheepishly and said, “There is some ... what is the English word? ... metaphor.”

***

China was worried about more than metaphor the following spring. In March 2008, riots broke out in Lhasa and spread across ethnically Tibetan regions, including Qinghai. Monks, workers, and the angry unemployed joined the fray, some peacefully, others violently. Over a dozen people died in Lhasa. Han immigrants were targeted by Tibetans who felt that the Chinese were unfairly reaping the benefits of the area’s economic stimulus, which on paper was intended for Tibetans. As the fire ebbed, ethnic tension was further stoked by the refusal of many Chinese to understand that Tibetans had just cause for discontent.

The first signs of trouble that year were in Tongren in February, during Losar. I returned to Tongren the following new year and interviewed a monk at the topmost temple of Longwu monastery, a hot spot of the protests. His recollection of the events the year before more or less corresponded with what I had read in wire reports and other eyewitness accounts.

During that Losar of 2008, riots were sparked by the smallest of quarrels. According to the monk, a Hui Muslim was selling balloons, one of which caught the eye of a passing Tibetan child. As it changed hands, the balloon flew up and away. The father of the child refused to pay three yuan for it, and the merchant was angry. Police officers tried to break up the ensuing fracas, but by then a large Tibetan crowd had gathered. The crowd felt the police were being too harsh on the nomad father and formed a circle to protect him from being arrested. Blows were struck, and the nomad was taken in. But later that night, against the backdrop of new year fireworks, a larger crowd—including monks from Longwu—threw rocks and protested, as much against pervasive injustice toward Tibetans as about this specific case.

After that night and the arrests that followed, the monk told me, the police increased their presence in the monastery, searching rooms randomly and smashing portraits of the Dalai Lama, even stealing hoarded money. “It felt like 1959,” he said, referring to the protests in Lhasa that culminated in the Dalai Lama fleeing to India. “Sure, I’m angry. But I can do nothing. What can I do?”

One year on, the festivities of 2009’s Losar in Tongren were decidedly chilly. In remembrance of those who died in Lhasa, locals refused to celebrate the new year with fireworks. Instead, the police lit their own fireworks and bribed other Tibetans to follow suit in an attempt to create an air of normalcy. Meanwhile, just north of town, the foundations were being laid for a new barracks of the People’s Armed Police. Control was tighter than ever. A short while before the night of the new year, Tashi introduced me to two monks who had been imprisoned for six months after having taken part in the Tongren riots. They were being tailed, they told me, and they couldn’t agree to an interview. In fact, they continued, the dormitory we were in was probably bugged. Tashi and I left quickly.

Afterward, in his brother’s office—his brother is a property developer, a lucrative business in expanding towns like Tongren—I asked Tashi what he thought of the riots of the year before. Up until that moment, we had never really talked about politics. “We all agree with the Dalai Lama,” Tashi began, “that the world needs peace, not violence. But the Dalai Lama doesn’t know about these things... . If you beat, beat, beat an animal, for a long time it can sit still. But it also becomes angry, and in the end it will fight you.”

“This is kind of a joke,” he went on, fired up, “but if I ever have power, I want to go to Obama or some other president, take a lot of new guns, fight the Chinese, and take my land again. Why can’t I do this? In Tibet, the highest leader is always Chinese. I’m Tibetan, but I had to study Chinese law and language and history. I can’t act like I’m Tibetan. I have to act like I’m Chinese, or I can’t get my school graduation receipt. And if I don’t know Chinese, I can’t find a job in my land, my motherland. In my own motherland, I have to speak Chinese.”

My natural sympathies were with Tashi—how could I side against such an underdog narrative?—but I couldn’t help thinking of the benefits he reaped from this new world he protested against. Tashi’s exwife’s son attended a school bankrolled by the local Chinese government. And just days before, we had visited a sick friend of Tashi’s at a refurbished hospital in Tongren. He was receiving far better medical attention than he would have were it not for the modernization that Chinese rule had brought with it.

Most of all, I thought of the school in Shuangpengxi where I had taught English a year and a half before, and of the kind of future my students now faced. When I was there, all classes were taught in Tibetan, and the children’s Chinese was poor by comparison. It was clear that they should have been focusing on their Chinese, not their English, if they wanted to get ahead in life. Now the school is under pressure to teach all its classes, except Tibetan and English language classes, in Chinese. It is not the only school in the area to feel such pressure. In October 2010, thousands of Tibetans took to the streets of Tongren again to protest this threat to their language and culture. But from a young age, the trade-off for Tibetans is between identity and opportunity.

After his outburst, I returned to Shuangpengxi with Tashi, camping on his floor the way I used to. I visited my old school and offered to teach a refresher English class for its students. Once so hospitable, the head teacher told me he must decline. My friends and I had been the last foreigners to teach there; after the 2008 riots, the local authorities had forbidden any more foreign teachers in Tibetan classrooms. The atmosphere was just as muted in the village itself. It was one day until Losar, and the residents all knew that their neighbors might be reporting on their behavior to the local police, whose presence was more noticeable and now included Han Chinese minders.

Instead of staying in the village, I climbed the high mountain ridge beyond the school with my girlfriend, with whom I was traveling. The ridge cut an irresistible silhouette, with stegosaurus contours culminating in a jutting outcrop of rock. We had been hiking for several hours and were resting at the top when we spotted a black dot below, climbing up toward us. Half an hour later, the dot turned into a man. He gave us the occasional friendly wave, his shouts lost in the winter wind. Another half hour and a flushed local policeman was with us, the very picture of good cheer, chuckling at how hard we were to find and asking if we would kindly come down with him to the police station.

What was this? Were we at an illegal altitude? Together we picked our way down to the valley, where—conforming far too neatly to ethnic stereotype—a thoroughly nasty Han minder awaited his beaming Tibetan deputy. In a back room of Shuangpengxi’s police station, the nasty minder sucked on a cigarette and rifled through the photos on my camera. Luckily, it contained the unoffensive one of my two memory cards. We were staying unregistered at Tashi’s house, he explained, and should move to the hotel for foreigners in Tongren that night and leave for Xining within two days. “Why?” we asked. “For your own safety ... dangran,” of course.

Of course, we weren’t the ones in trouble. Tashi told me later that he didn’t get more than a slap on the wrist from the police, but suffered a lasting humiliation in the village when his neighbors misinterpreted the police car outside his home and assumed that he had stolen something. I felt terrible and asked if he knew who had told the police we were staying with him. I had assumed it was a neighbor, but the truth was worse. Tashi’s own brother had informed on him. He had been in the room during Tashi’s earlier tirade and disapproved of such a cavalier attitude with foreigners, no doubt among more self-serving motives. Not every Tibetan, it was evident, remains eternally loyal to Potala Palace.

***

That was the first of two betrayals of Tashi that winter. The second cut much deeper. Before leaving our police-approved hotel in Tongren, we snuck back into Shuangpengxi to say goodbye to Tashi. At that point, he was set to be married to his girlfriend Lhamu in just a few days—Losar being an auspicious time for unions. But two days later the call came in Xining. “She left me, brother. Please come quickly.”

Lhamu (also a pseudonym) is an unassuming policewoman with a shy, low laugh. She was born into a relatively well-off family in Shuangpengxi and is a bit shorter than Tashi, with the characteristically strong build of Tibetan women. She and Tashi had been together for two years, through which she was unwaveringly patient with his restless wandering and his roving eye for other women. They shared the same sense of humor, loved each other, and had been talking about marriage for some time.

There were initially two problems with this idea. Problem one: An obscure village law said that no man could remarry within the same village. Tashi’s childhood wife was also from Shuangpengxi, so the elders of the village said he had to look further afield for a second bride.

Tashi came up with an ingenious solution for this. Knowing that the only thing village elders believe in more than tradition is religion, he went to get the blessing of the nearest incarnate lama. Incarnate lamas aren’t to be found just anywhere, mind you. We had to drive a full forty minutes down the valley to a monastery where an octogenarian incarnate was supposedly in deep meditation. Together we performed the preliminaries—a full circuit of the monastery, turning every prayer wheel on every stupa in three clockwise circuits—before we came to the central temple and gave the door a rap. A monk came out. Tashi delivered his pitch. A brief exchange. The monk went in. Fifteen minutes later, he emerged with a piece of paper from the lama, not larger than a fortune cookie slip. Written on it, with the directness of someone in his eleventh life, was: “Pray to Buddha once in the morning, once in the afternoon, and once before sleep, and this marriage will be successful.” It was good enough for the elders.

Problem number two was both more familiar and a tougher nut to crack: Lhamu’s parents hated Tashi’s guts. They thought he was a layabout. He rarely stuck with a job for longer than a few months. He never visited his mother and father, even if he was devoted to his grandmother. He dressesdlike a Chinese yuppie. His long hair was often tinged with artificial red. And he was almost always away from Shuangpengxi, in Xining or further afield.

When he visited me in Beijing, Tashi painted a tangka on the wall of my flat, rather oddly depicting me as Buddha floating above Shuangpengxi. Then we would go out, and he would flirt left and right. In the American-style bars of the student district where I was learning Mandarin, he tried his luck with Western girls and texted old flames. When I showed him how to bypass the “great firewall” of Internet censorship, he first asked me to look up Radio Free Asia, which he heard had reported truthfully about the 2008 riots. Next, he googled “American girl sex”—which he had heard was more experimental than Tibetan girl sex.

At the eleventh hour, Lhamu—who had agreed to the marriage against her family’s wishes—caved into parental pressure and decided that Tashi would make a poor husband. He learned of her decision one day into the year of the ox, when he saw her walking hand in hand with another man.

The humiliation of this breakup was so great that Tashi did not feel he could show his face in Shuangpengxi. He moved back to Xining, and threw himself into a more Chinese pace of life. One new venture was a monastery being built in the south of Qinghai, funded by a Californian millionaire and born-again Buddhist. Another was the impractical idea of selling Tibetan yak and sheep wool direct to factories in southern China—a business that has long been the monopoly of Hui Muslims in the region.

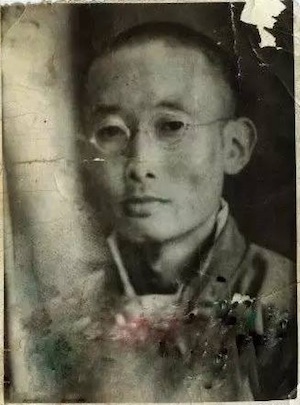

Tashi once told me his role model was Gendun Choepel, a famous twentieth-century Tibetan monk whose face appears on mouse pads from Lhasa to Tongren. Like Tashi, Choepel was born in Shuangpengxi. The school where I taught is named after him—Gendun Choepel Middle School—and its gatekeeper claims to be his direct descendant.

Tashi once told me his role model was Gendun Choepel, a famous twentieth-century Tibetan monk whose face appears on mouse pads from Lhasa to Tongren. Like Tashi, Choepel was born in Shuangpengxi. The school where I taught is named after him—Gendun Choepel Middle School—and its gatekeeper claims to be his direct descendant.

Choepel is sometimes called a “rebel monk.” In the 1920s, as a young man, he befriended a Christian missionary despite his family’s warnings that his hair would turn blond and his eyes blue. As a monk, he was open about his drinking, smoking, and love of women. Later in life, he traveled to India, where he translated the Kama Sutra into Tibetan, writing that “if natural passions are banned, unnatural passions are grown in secrecy.”

In Choepel’s time, Tibet was tragically missing the opportunity to modernize. The death of the progressive thirteenth Dalai Lama returned power to reactionary elites. The 1930s could have been the moment in history when Tibet secured its lasting independence from China. But history went the other way. Vocal in his criticism of the status quo and a founding member of the Tibetan Revolutionary Party, Choepel was accused of being a communist spy, spent three years in a Lhasa prison, and died shortly after his release. He lived just long enough to see Chinese troops “liberate” Tibet in 1950.

Tashi is no rebel monk. He may drink and sleep around as much as Gendun Choepel did, but he lives in a very different Tibet. Choepel wanted to see Tibet change on its own terms. Sixty years after his death, it has changed on China’s. It has more than its fair share of injustice and ethnic inequality. But it also has new hospitals and schools, a modernized infrastructure, and opportunities for success for Tibetans who play by China’s rules. Tashi, along with so many of his generation, embraces those opportunities with the same breath that he protests against their inequalities.

It was a long time coming, but Tashi’s mental journey away from his Tibetan heritage and toward a world of new possibilities in China or abroad was thrown into sharp relief after Lhamu left him. Sometimes we talk about Lhamu, and Tashi tells me that he wants a foreign girlfriend next. He used to say that he would take a Tibetan wife, or else he might lose his identity as a Tibetan. He used to say that he would always live in Qinghai—before he became alienated from his home village. Now he dreams of living in London or Paris, or of being a professor of Tibetan history, but in a Chinese or overseas university. In short, he wants to get out of Tibet.

***

It is summer, a year and a half after that tumultuous Losar of 2009, and Tashi and I are together in Shuangpengxi again. Leaving Tibet is no easy matter for him, and whenever I am there, I don’t want to leave. I have finally climbed that high ridge—with no police interruptions— and command a sweeping view of the village. The scene looks much the same, with one addition: a new China Mobile tower rises high over the police station. Making use of full signal, I text Tashi that I’m coming down for tea.

Shuangpengxi is all but deserted at this time of year. Mid June is high season for picking caterpillar fungus, called “winter worm, summer herb” in Chinese or yartsa gunbu in Tibetan, which is highly valued as so-called "Himalayan Viagra". If you have a keen eye and the patience of a Buddha, the high plains of Qinghai are among the only places to find it sticking up a half inch from the brown earth. One season’s harvest can be worth several times what a Tibetan farmer earns in a year. Every able-bodied man and woman in Shuangpengxi is away from home, caterpillar hunting. But that is not so drastic a change from the norm. In small villages across Tibet and the rest of China, droves of adults are leaving to work in big cities. Shuangpengxi is swift becoming a ghost village of children and the elderly.

It is dusk when I reach Tashi’s house, which he built himself out of stone, sand, clay, mud, and wood. His grandmother, bent double like a crowbar by the weight of her seventy years, greets me with a toothless smile. I step through a small courtyard to the kitchen, where she puts a charred kettle on the fire and lays out a bag of roasted barley and three bowls. We each take a handful of barley, add warm water and a generous chunk of yak butter (I ask for extra sugar), then knead the mixture until it’s about the size and consistency of a stress ball. Tsampa. Gulps of yak butter tea help it down.

After we have eaten, Tashi lights a cigarette, takes a terrifyingly long pull and exhales endlessly, then sucks the smoke back through his nose for another inhale. He grins at me and lifts a bag from a hidden nook. It clinks and sloshes with the sound of beer.

•

Alec Ash is a writer in Beijing, and founding editor of the Anthill. His book Wish Lanterns (Picador, 2016) is available at the Beijing Bookworm

This story first appeared in Chinese Characters (University of California Press, 2012). Tashi's poem has also been published on High Peaks Pure Earth